What! My Kids Started Finnish School & Mostly Play

How is it possible for Finnish kids to outsmart most of the world when school starts at 7 years old, days are much shorter, and play is at the center of learning?

Hi Friends! Hope you enjoyed your Halloween:-) Halloween has taken off in Finland in the last couple of years, but only in the form of little school and daycare parties. My boys really wanted to go trick and treating, and even though the custom doesn’t exist here, I found two other parents whose sons—my boys’ classmates—wanted to also give it a try. This version of “trick & treating” meant ringing random doorbells in the Art Nouveau-style apartment buildings lining the streets of the dark, foggy city center. With their costumes on, they surprised the non-suspecting residents with “karkki vai kepponen!” (=”treat or trick!”).

Considering it was pure luck that anyone had any candy in their kitchen cabinets, the sweets hunt was a major success. And as the four boys roamed the buildings from top to bottom, one of their mom’s and I had a chance to chat about Finnish schooling as we lingered in each main entryway.

My only (blurry) pic from the Halloween disco!

I don’t understand how it’s possible that Finnish kids surpass most others in the world around the age of 15 in academics when they essentially “learn so much less”? Why do you think that is?

In the US, my boys’ 2nd grade school week was 30 hours; here in Finland it’s 22 hours—and that time is even fully focused on academics: there’s also a lot of play.

You might have seen this in the news globally over the last couple of years, but Finland has become a sort of a phenomenon in education because of its consistent top ratings in reading, mathematics, and science literacy in The Program for International Student Assessment (known as PISA), which students take at the age of 15, to compare education in different countries. Even though Finland fell from its number 1 spot in the latest test, it’s still way above the US and the UK for example, that rate 12th and 13th.

The way Finnish kids learn is different, the mom said. It’s learning through play. That’s how you learn all the most important things: negotiating, problem solving, conflict resolution, relationship-building, creativity, and figuring things out on your own. The math or writing—that’s just technical.

Teacher Calls, Concerned

I got introduced to the American education system when I was pregnant with my first son in New York City, and learnt that I had to quickly, following birth, get him a spot at one of the coveted 2-year-old programs, which where gateways to acceptance in higher grades and highly rated schools.

During my son’s 3-year-old program, I might have offended his teacher when I finally dared to ask: “when does the real school start?” In Finland, school officially starts at the age of 7, with first grade. “This is school”. I should have figured! It was called “preschool” after all.

When one of my sons progressed to the kindergarten grade, which is the class for 5-year-olds, and considered the preparatory class for first grade, his class was spending a lot of time learning to read. I found it slightly odd (he was 5 after all!), but thought, hey, reading is super fun, and early exposure to letters and sounds without any pressure could only be a plus.

Until I got a concerned call from his teacher, asking for a meeting.

DISCLAIMER: I very carefully chose the schools my boys went to in the US, and was extremely lucky to be able to do so. I respect and value and simply love all the teachers my boys have had, and in fact keep in touch with many of them. I know they have always had my boys’ best interests at heart. I’m sharing these stories to reflect on the vast differences in the educational styles and attitudes. I think it’s eye-opening to learn from different cultures, so we can then make choices on how to adjust our own mindsets, if we feel a change would serve us better.

Brain Testing When a 5-Year-Old Doesn’t Read

My son’s teacher told me that a psychologist had visited the school and done her yearly assessments on student learning, and had become critically concerned about one of my son’s because he wasn’t reading at the level of some of his classmates. No other issues were concerning. Brain tests were recommended to identify a learning challenge. The psychologist was especially concerned that other kids would make fun of my son if he wasn’t as skilled as they were.

I took a deep breath.

Look, I value the opinion, but I am not concerned. My son is not only just 5, but he’s also tri-lingual (in NYC, he had gone to school in Spanish). For example, I learned the alphabet at the age of 7, and became a journalist published in numerous notable publications in two languages, and an author, and an entrepreneur. It’s also well documented that multi-lingual kids learn speaking and reading later than others. I think we just give him time.

The teacher agreed to speak about it with the psychologist. And came back with the same strong recommendation to start brain testing.

I called the suggested testing practitioner, and as health insurance would not cover the tests, it would cost us $5,000 and be a several-day-long series of tests: both an astronomical expense and a lot to put a 5-year-old through. I then proceeded to get second opinions and two other practitioners told me that if there are no other concerns, testing would very likely not be necessary.

Going back to the teacher, I asked what the outcome would be, should they identify some kind of learning challenge. “A tutor.”

I said we would not pursue testing, but would agree to a month or two of once-a-week tutoring (which we would need to cover), as long as our son would have fun with it, and not find it too stressful.

I’m happy to say, she agreed with the strategy and by the time my son started first grade, he had naturally grown up a lot, and caught up.

This features the boys’ typical school, 8:30-1:30pm: class, recess, class, lunch, class, recess, small group class for half the class (the others get off at 12:20).

Heading to the Principal’s Office

Pouring my husband and I a cup of black drip coffee, with oat milk, the Principal of my boys new Finnish school contemplated the question of when he would get concerned if a child wasn’t reading. We had met with him purposefully to get an answer to the question: “how can our kids learn if their day is so short and a lot of learning is through play?”

We are not concerned about reading until the child is in the 3rd grade. Everyone develops at their own time. You can’t rush it. If they still have a hard time, we get them extra help, at the school.

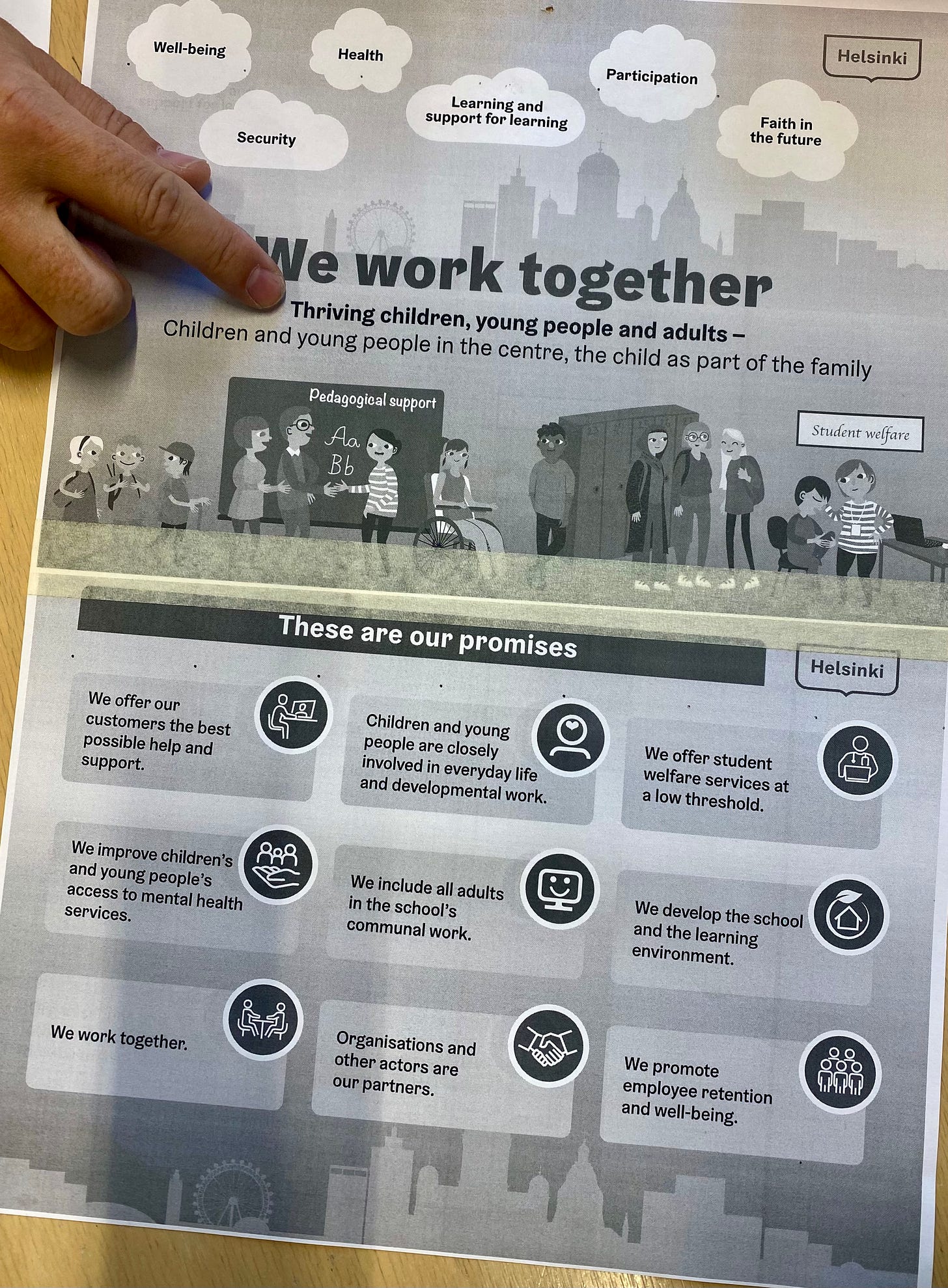

The principal then showed us the 6 pillars of Helsinki’s elementary education (Helsinki is the capital of Finland):

well-being

security

health

learning and support for learning

participation

faith in the future

I was surprised to see learning as only 1 out of 6 pillars. To add to that, there are no standardized tests in Helsinki until the age of 18, when you take your matriculation exams.

How are the students assessed then, if there are no tests? My husband asks.

The Principal offers us cake (In Finland, just as in other Nordic countries, coffee is served always and everywhere, often with something slightly sweet), and sits back around the round table in the teachers lounge where we are gathered, and thinks for a minute.

Each student’s grade is based on many factors. It’s really about the progress and participation. Are they completing their different projects? Is the child participating in the class, engaging with the other students and the teacher? Is the child independently doing their homework? (The Finnish homework takes about 10mins max, per day. Teachers don’t usually give homework for the weekend).

He continued to explain that the focus is developing the whole child, not just academic skills, but social skills and independence. The students are not expected to learn or master concepts at the same speeds. Of course, no system is perfect and Finns themselves would point out many challenges, but in general, the system produces wondrous results.

Observing a Lesson.

I got my first-hand look at a Finnish classroom when all parents were invited to come to observe—and participate. I was so curious to see how the kids learn Finnish reading and writing, but we didn’t do any academics!

We played games that taught negotiating, accepting and not judging but adding to other people’s ideas, and identifying our own emotions. And we did a craft together.

Later, when I started getting the teacher’s weekly updates, besides identifying what the class was working on in math and reading, she also told us about a wide range of other themes they had been practicing:

We have also played games that helped us learn how to support and motivate each other, how to understand what makes us feel good and happy, and what the sources for our wellbeing are.

This poster in the boys classroom identifies positive emotions the kids had gathered: joy, being surprised, motivation, peace, admiration, amusement, security, friendliness, gratefulness, curiosity, pride and love.

Parents Role

Besides the focus on play, the Finnish school system has another surprising difference: parents’ involvement. Besides the school offering free lunch and kids walking or biking to school on their own, parents also don’t participate in their kids’ minimal homework. Parent Associations do exist and arrange fun community happenings—like the boys’ school’s recent Halloween disco!—but beyond that, the school doesn’t ask anything extra of the parent nor do the parents feel like anything extra is needed.

In NYC, tutors even for 4-year-olds is common (and I actually discovered only after we had moved out of the city, that most parents I knew did have a tutor for their kids, again to secure best possible placement in the next school; and the trend is not unheard of in Connecticut, or other States either, as long as you can afford it: it simply helps you keep up or advance your classmates and therefore puts you ahead as a lot, if not everything, depends on the standardized test scores you get. Parents are also invited and to a degree, expected, to participate in homework, school events, school programs and take on developing a lot of the skills outside academics. It’s a different way of learning.

PS. Hi! Don’t forget to tap the heart-shaped like button at the end! It’s like saying hello back:-)

Secret to Success: Play, Joy & Independence?

Being somewhat “Americanized” parent, I have helped my boys with their language homework here, mainly because they still don’t fluently read Finnish, and I did hire them a tutor—a Finnish language tutor—to make it easier for them to keep up with their new Finnish classmates. In that sense, I’m here doing exactly what many American parents want for their kids in the US and some other countries: master their homework, and feel successful in the class.

But I must also admit that the idea of backing off, and just letting our kids learn at their own pace, without intervening or supervising, is wildly attractive to me—and as I have found out, also for my kids. It’s what everyone else here does, and the results do speak for themselves.

“The Finnish education—and parenting for that matter—teaches kids to be independent and then to make their own way,” a TV producer friend and a mom of three said, “it’s not to make sure they are the best or number #1, which is more the American idea, that you teach or parent kids to succeed.”

But maybe these two opposing ideals are not so much at conflict with each other after all. Is there anything better for confidence than learning what you are capable of, on your own or falling in love with learning when you are really ready for it?

With that, I’ll certainly take a note or two from the Nordic playbook even when we return back to the States.

Let’s Chat! I would love to know what you think of this wild idea of learning through play. And I wonder what would happen, if you are not in Finland, if you didn’t aid in kids’ homework at all and just let them learn at their own pace no matter the scoring? Is that a road to ruin? Can we take this Nordic mindset to the educating kids with joy and play anywhere else?

x Annabella

I think one of the biggest flaws in the high stakes testing American system is that it has completely discounted the importance of schema and all of the interpersonal skills that early Finnish schooling seems to prioritize. Having an understanding of the world and the vocabulary to explain and understand is so important for literacy, critical thinking, and understanding that math word problem 🙄. I have seen it from both sides as a parent of gifted kids, whose reading skills have been buoyed by their understanding of the world. And as a reading specialist, working with students who struggle with vocabulary and decoding longer words because they have not had the same oral language exposure. Let alone the skills they are tested on, like identifying theme and making conclusions. It is an overwhelming task to remediate!

Hi! So as a Finnish mother, I have to point out that not all homework takes 10 minutes, some kids need help from a parent, and we do have tests in Finnish schools but not in the lower grades. My kids school started having ”real” tests in the third grade (test grade scale 4-10). I would say on average homework in our household takes about 20-60minutes. But short school days, yes, and focus on so much more than academics, yep! My son is now in 5th grade and his school week is 27 hours long which is kind of ok. 3 hours of phys.ed/week.